If you pick up your mobile phone, you probably see a lot of apps you were excited about when you first installed them. Maybe we started using those apps at first, but over time realized they didn’t do exactly what we expected. For teams building those apps, that’s not exactly a recipe for success.

“As product people we don’t want to create products that you’re just going to install. We want to create products that are going to create value for you in the long run. That’s what leads to successful products,” product discovery coach Teresa Torres said at a recent ProductTank Waterloo.

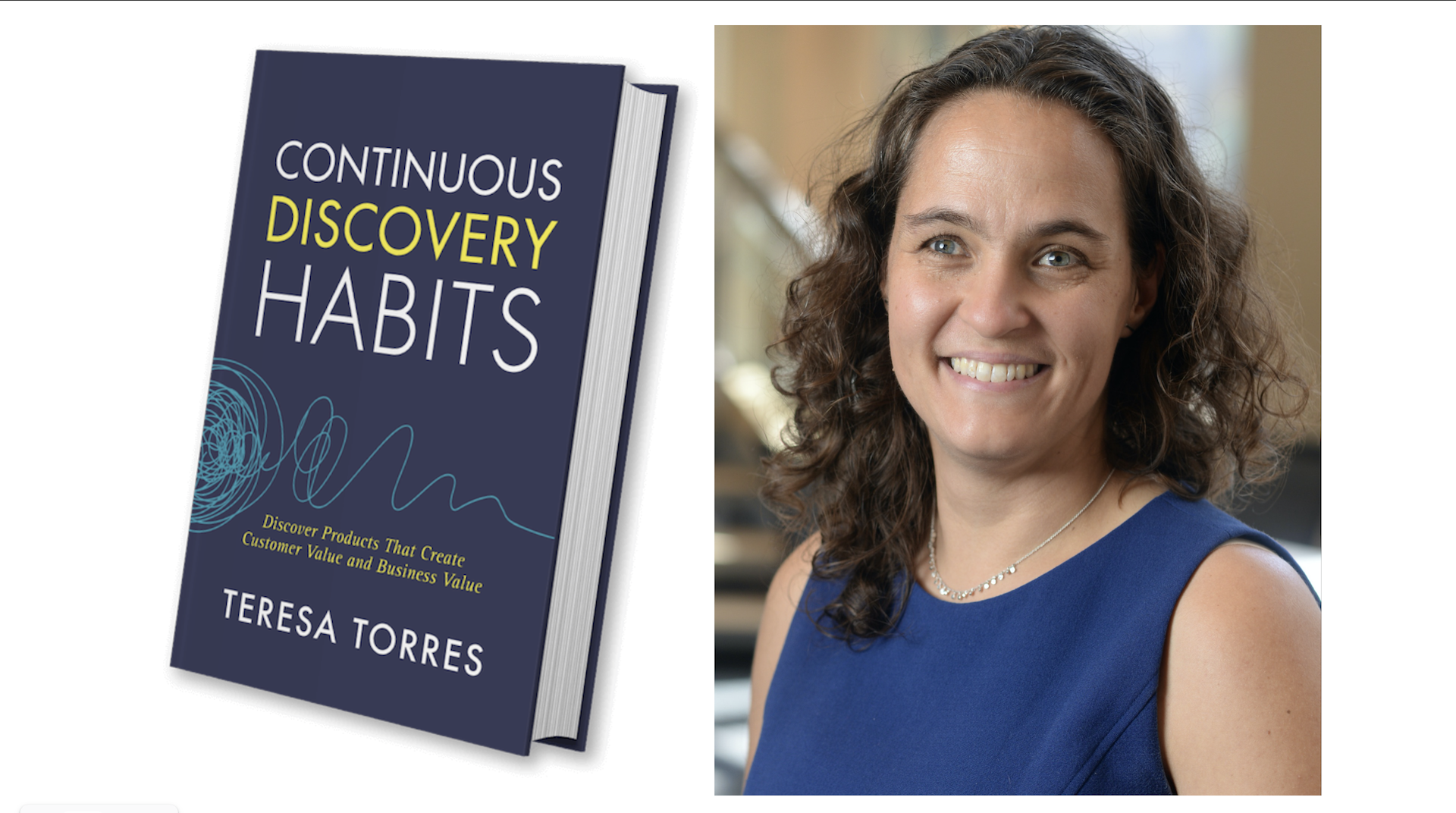

Torres, who recently published a new book Continuous Discovery Habits: Discover Products that Create Customer Value and Business, joined the virtual meetup to share the tips and tricks she uses to help teams she coaches build successful products.

The key to building successful products is to shed our project mindset and adopt a continuous discovery one, said Torres. A project mindset is where teams kick off a new project, interview a bunch of users, write a research report, decide a direction based on the research, design the product, conduct usability testing, then hand everything off to engineers to build. Sound familiar? It’s how most teams work now, said Torres. Though there isn’t anything wrong with that — it’s better than doing no research — it’s not ideal.

“What we’re seeing is as our delivery cadence becomes more continuous, as we release more frequently, as we release in smaller batches, we’re seeing that our discovery methods need to change to match that cadence,” she said.

That’s where continuous discovery comes in. Continuous discovery, said Torres, is when the team building the product has weekly touch points with customers, where they conduct small research activities in pursuit of a desired product outcome.

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

Talk to customers weekly

If you do nothing else, talk to customers weekly. Torres said because product teams are making decisions about their product every day, they need to make sure they’re talking to customers weekly to better understand which opportunities to pursue and which outcomes to strive for. We know the importance of customer interviews and user research when it comes to big decisions, she said, but it’s important to get customer feedback for medium and small decisions too.

That’s because product management suffers from the curse of knowledge, said Torres. Product people know their product inside and out and can’t remember what it’s like to not know everything about it. But customers don’t have that same knowledge about our products. That curse of knowledge leads us to make decisions from our perspective, rather than our customers, and we end up making decisions that don’t work for them (hence, the apps on your phone that you don’t use). The easiest way to overcome that, said Torres, is to talk to your customers weekly.

If you’re not doing that now, build your customer-engagement muscles gradually: Start by talking to just one customer quarterly. Then progress to monthly talks, then weekly talks. The more you talk to customers, the more you’ll close that gap between how you think of your product and how your customers think of your product, she said. And sharing what you’re doing early with customers makes it easier to course-correct along the way.

The role of product trios

Now that you’ve decided your product team needs to talk to customers, who on the team should talk to them? The product manager, design lead, and tech lead — a group that Torres called the product trio. You might have a bigger team than that working on the product, and that’s OK, said Torres — they’ll still be looped in. But the cross-functional team leading the discovery should be small and nimble so it can make decisions quickly.

(Three white circles on a blue background denoting the product trio: Product manager, design lead, tech lead. Other roles appear in the margins in transparent circles.)

The product trio is leading the discovery so they’re responsible for engaging with customers and closing the curse of knowledge gap. Other team members can still be involved and follow along with what the product trio learns. The goal, said Torres, is that by the time you give engineers requirements for what they should build, they shouldn’t be surprised because they’ve followed along on the whole journey.

But how do you decide what to build?

How an opportunity solution tree will drive outcomes

Talking to customers weekly is great, but all that research only benefits your business if you actually use it to drive an outcome that’ll create value for your business.

“I’ve talked to teams that talk to customers all the time, they create beautiful experience maps, they know a ton about a customer, and they haven’t shipped anything in a quarter,” said Torres.

There’s an easy way to make sure the activities you do align with a desired outcome: Use an opportunity solution tree. An opportunity solution tree helps you focus on an outcome mindset versus an output mindset, said Torres.

“With the pace of competition and disruption of technology, we’re seeing we can’t always predict what we should be building next month or three months or six months from now. There’s a lot of ambiguity and we’re not always getting it right, we’re recognizing we need to experiment our way to the right solutions,” she said.

Instead of deciding upfront which outputs you want to build for your new product, and then validating them, focus on which outcomes create value for your business and customers.

(Blue, green, yellow, and orange rectangles with arrows pointing down a decision tree. Text: Opportunity solution tree. Define a clear desired outcome.)

It’s a big shift in thinking, said Torres. Outcomes force you to think about business value. Companies over focus on creating customer value, said Torres, but we need to create customer value in a way that delivers business value. “If you don’t, you will go out of business,” she said.

Outcomes usually centre around the health of the business. So if you were a streaming service, a business outcome may be to increase subscriber retention. Your product team would then need to translate that into a product outcome, such as increasing viewer engagement. If people are watching more on your streaming service, they’ll likely continue to subscribe because they’re getting value from your product.

And here Torres added a word of caution: You’re not trying to trick people into watching more of your streaming service. It’s important to create products in an ethical way, because that’s what leads to long-term customer retention and, ultimately, a successful product. Instead you want to explore opportunities that would create both business value and customer value in an ethical way.

“We’re looking for opportunities to intervene in our customers' lives,” Torres said.

It’s only once you decide which opportunities you’re going to pursue that you veer into outputs (what Torres called the solution space).

Mapping out the opportunity space

There are two key research activities for teams to do every week, said Torres. Interviewing customers is the first easy way to map out the opportunity space. You’re not interviewing them to explore solutions or get feedback, she added. You’re interviewing them to get to know them and uncover opportunities. If you’re not sure how to recruit them, Torres suggested asking them while they’re on your website, or putting out a call in your newsletter, and offering customers a small incentive to participate.

“The vast majority of teams I’ve worked with have successfully implemented this method,” said Torres.

If you’re working on a product or service sold to other businesses (B2B), that approach won’t work. In that case, you’d use your customer-facing teams to recruit participants for you. Do that by telling those teams, when they speak to a customer that has X need, ask them for X amount of time, and offer them X reward. The key, said Torres, is you want to make it very easy for customers to say yes, so offer them a good reward in exchange for a bit of their time. A good reward for B2B clients could be access to your premium service, a discount off their services, or access to a white paper about key research, she said.

If your market is small or hard to reach, create a customer advisory board and meet with them over time. If you interview a different member of your advisory board each week, you’re getting the customer engagement you need to close the knowledge gap without burdening a single person.

You have a customer in the room, now what?

As you start to interview customers, make sure you're asking the right questions. Interviewing can be challenging, but there’s a lot you can learn from them if you plan and run interviews the right way. Frame your question so it isn’t too broad. So if you’re interviewing customers for a streaming service, you don’t want to ask: How do you decide what to watch? If someone fancies themself as a person who watches documentaries, then you’ll hear about that, but not about the shows they watch regularly.

“We tend to answer direct questions from our ideal sense of self,” said Torres. “The problem with this is we don’t want to build products for ideal selves. We want to build products for actual behaviours because that’s what leads to long-term engagement.”

One way to find out about your customers’ actual behaviour is to frame questions to encourage storytelling. So instead of asking, “How do you decide what to watch?”, instead ask, “Tell me about the last time you watched our streaming service.” That way, you’re collecting stories about a specific experience and the answers you get are much more reliable.

Interested in learning more about how to interview? Check out 10 UX interviewing tips from a journalist

Working with sets of solutions

Every product team should get in the habit of working with sets of solutions, rather than one idea at a time, said Torres. When you work with one idea at a time, you never know if the results you get are good enough because good is a relative term. And you’re susceptible to confirmation bias because you’re more likely to see evidence that supports your idea and ignore the results that don’t.

But when you work with sets of ideas, you can compare results and check your confirmation bias, she said. Comparing and contrasting gives you clear results, she added. When you do it though, make sure you come up with three solutions that all target the same opportunity and solve the same customer need.

Once you have those, there are a few simple methods to evaluate ideas that unlock compare and contrast decision-making, said Torres.

Don't test ideas, test assumptions

When you’re working with sets of solutions, project-based research won’t work, said Torres. You can’t do A/B testing on sets of solutions and you can’t create an end-to-end prototype of all three and then get feedback from users.

“That would take weeks and we don’t want to take weeks evaluating solutions for one opportunity,” she said.

Instead, you want to test your assumptions. It’s faster to test assumptions than whole ideas, she said. It’s not a new concept. Eric Ries wrote about testing assumptions in The Lean Startup. And testing assumptions is a key part of product validation.

Assumptions fall into a familiar set of categories — desirability, viability, and feasibility. Torres said she adds usability assumptions and ethical assumptions to that set. It can be hard to see our own assumptions, she said. But Torres offered a simple strategy to surface assumptions: story mapping.

“People usually story map to communicate requirements. I want you to story map much earlier in the process,” she told the group who attended ProductTank Waterloo.

Think of it as your crummy first draft, she said, and start mapping out assumptions. Assume the solution already exists, but story map what your customers have to do to get value out of your idea. What needs to be true in order for your customer to take the next step?

So if you were a streaming service and wanted to see whether incorporating live sports would help you retain customers, you might work with a set of ideas where you’re considering either partnering with a local channel, partnering with another streaming service that already offers live sports, or partnering with a sports league. Your first step in the story map for each scenario would be to assume that people want to watch sports. The next step would be to assume that they want to watch it on a streaming service (versus television). And so on.

(Five columns of squares outlining steps Netflix subscribers would have to take to watch local sports through the streaming service. Text along the top: Story maps help us see our assumptions.)

Some assumptions will be shared across all three ideas, which is fine said Torres because those assumptions will either support or eliminate a set of ideas. It’s actually why assumption testing is faster than idea testing, said Torres. You get to learn about sets of ideas at once. Some assumptions will distinguish solutions from each other and that’s when you compare and contrast decisions.

3 easy ways to quickly test your assumptions

You don’t need a lot of time to test your assumptions, said Torres. Once you have them, you can test your assumptions in a few hours, or a day or two.

One way to test your assumptions quickly is to create a small prototype. With the streaming service and live sports example, you could test the assumption that people want to watch live sports on a streaming service by mocking up a screen that has a mix of TV shows and sporting events and ask people what they want to watch right now. If someone’s a sports fan, you’d expect that they sometimes want to watch a sporting event.

The second way to test assumptions is with a one-question survey that asks about a specific instance in the past, for example if someone has watched sports in the past week, or month. That question could appear as a pop-up on your website, said Torres.

The third way to test your assumptions is to look at the behavioural data you already have. So, with the streaming service example, you could search your query database to find out if people are looking for sports when they search for what to watch next.

You can test the vast majority of your assumptions using these three ways, said Torres. The one exception is that a lot of feasibility assumptions are going to require a research spike — where engineers investigate a specific assumption for a set amount of time, such as whether you could integrate a local channel’s feed into your streaming service.

In the end, as instructive as Torres’ ProductTank Waterloo talk was, it was only an overview of the continuous discovery activities that frame product strategy. They're all outlined in her book, which Torres calls a workshop in itself.

“I wrote this book to be a hands-on practical reference guide for product trios who want to work this way,” she said.

Read more about Torres and the courses and workshops she offers to help teams make better product decisions at Product Talk Academy.