About 20 years ago, my spouse and I travelled to Paris. I remember riding the metro everywhere. It was simple enough for me to understand even though I didn’t speak French: Look at the coloured line on a map, match it with the coloured symbol at the front of the train, and off you go to explore the City of Lights.

Good design makes the world a better place to live. And yet bad design is still everywhere — from educational systems to the healthcare system in the U.S. that people depend on, says bestselling author and former project manager Scott Berkun.

“The world is a mess,” says Berkun. “And the amount of people who understand how to look at those things and make them better using what we know from 10,000 years of designing things is small and that’s a problem that should be solved. More people should understand how to look at problems the way a designer would.”

Those badly designed experiences and systems, and Berkun’s desire to get people to ask better questions and look at problems the way designers would, is what compelled him to write his latest book, How Design Makes the World.

Berkun learned about design in college. He didn’t have the word designer in his job title for most of his career, but he’s always used what he learned in design to “solve just about every kind of problem,” he says. He wrote the book as a way to give people stories about design — from seatbelts used in cars to airport layouts — so that they can start to see the world the way designers do. There’s even a handy checklist of questions at the end that people can think through the next time they come across a bad design experience.

Our brains are built for survival, says Berkun, but asking questions can get our brains to flip modes so that they’re also powerful and inquisitive. Berkun included the checklist at the end of his book to help people make that switch.

“If every time someone says they love something or they hate something and you give them that checklist, now they can articulate that love or that hate in a way that’s far more powerful and far more useful for themselves and recognize, ‘Oh this is why I hate this,’ ” he says. “It’s a way to elevate the level of discourse people have in how they experience things in the world. Even if they never design anything themselves, they’re now more informed about how design gets done and that makes them more articulate and more likely to get what they want out of everything they interact with in life."

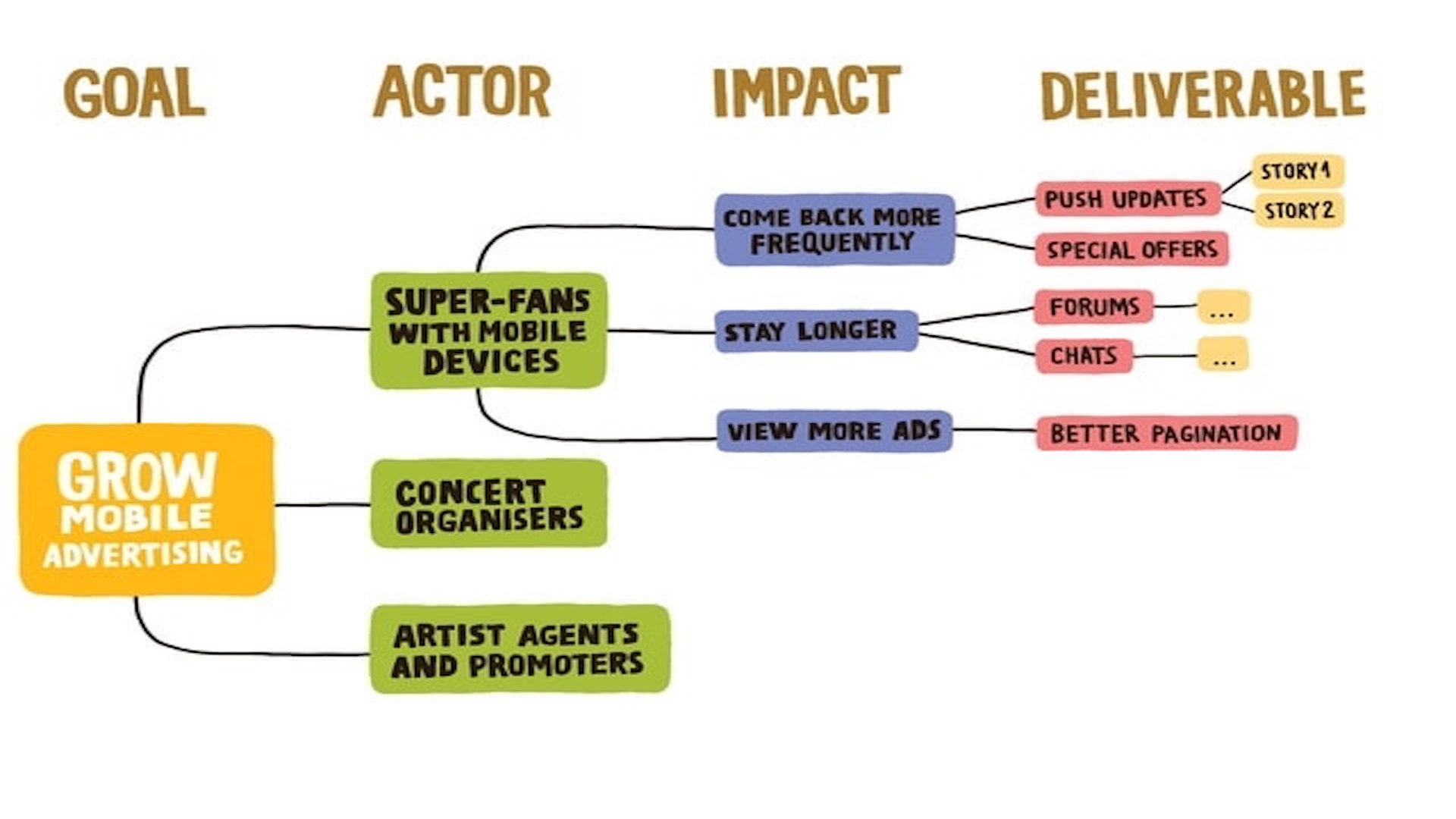

The book’s goal is to get people to ask better questions so that they make better decisions about what they buy, use, and make. It also looks at the power designers have to influence organizations through their work, and ethics around the addictive nature of designed experiences, such as casinos and social media. The book pokes at the idea that what’s in your self interest may not be in other people’s self interest, says Berkun. That’s not a new problem, he says, but every time you make something for someone else to use you’re inheriting some ethical challenges.

“In this era, the most prominent way for that to be recognized is social media,” Berkun says.

The best way to change that, he says, is for designers to put themselves in a position of power.

“The ethical decisions then become yours,” he says.

Most designers aren’t necessarily interested in climbing the corporate ladder though. But there is an alternative: Become good at persuading people, organizational politics, and making allies, says Berkun.

“Those are all skills that anybody can get better at and that means you don’t have to be the (vice president) and don’t have to have all the power, but if you're really good at persuasion and reading the room and finding allies and making the right play at the right time you can be really influential and have a lot of granted power,” he says.

Berkun will be talking more about how designers and user researchers can influence their organizations and sharing lessons from his latest book at a joint uxWaterloo and ProductTank Waterloo virtual meetup Nov. 19.