The pandemic has exposed a new set of wicked digital problems while exacerbating ones that already exist.

COVID-19 is casting a harsh light on inequities created by technology — whether it’s kids falling behind in school because they don’t have equal access to devices or seniors who are food insecure because they couldn’t afford to stock up during panic buying and now struggle to shop for groceries online.

Wicked digital problems were brought to the forefront again recently when a Black man in Detroit was wrongly arrested because facial recognition technology falsely identified him. It’s the first known case of a wrongful arrest because of the technology, but research has shown that problems exist with machine learning, especially for people of colour.

MIT researcher Joy Buolamwini, who founded Algorithmic Justice League, studied commercial facial recognition technology and discovered it was biased, accurately identifying light-skinned males more consistently than darker-skinned women. She found at one point the technology was so inconsistent for the darkest-skinned women that it’s ability to even accurately identify gender was a coin toss.

“Machine learning has proven itself in the last just five years that it has no regard for Black people,” said Lola Oyelayo-Pearson, Shopify’s Director of UX, Multichannel, who talked about the reality of wicked digital problems, new and emerging, and what designers can do about it during a segment of Fluxible TV. “As a Black woman if, for whatever reason, I was interacting with a machine learning algorithm in a civic sense, my outcomes are going to be worse because the automatic rules will be based on historical data and historical data shows as human beings, we don't regard people who look like me and we don't regard them very highly and … we don't treat them in the right way.”

Wicked problems are complex

Design theorists Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber first coined the term “wicked problem” in 1973. It refers to complex social problems that aren’t easily solved — historically, social issues such as poverty, crime, and education policy, but more recently, climate change has also become another example. Wicked problems are unique and often a symptom of other problems, Rittel and Webber said in a landmark paper entitled “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning” published in the journal Policy Sciences.

“The thing that always struck me about thinking about wicked problems is they're man made,” said Oyelayo-Pearson. “They're wicked because they're defined in lots of ways by our own failings, by the systems and the kind of environments that we cultivate, our political systems and economic systems. They essentially create wicked context, and they create the situations where wicked problems exist.”

Oyelayo-Pearson said she first read about wicked problems when she was at a frustrating point in her career. She felt as though what she was trying to accomplish was “infinitely undoable,” she said.

“It felt like there was just no hope in the sky. There wasn't a project that made sense. You couldn't put together a plan. You couldn't do research and say, ‘Hey, this is the right direction’ and then make that piece of research happen. It just felt super frustrating to continuously be trying to solve a problem and never be able to solve that problem,” she said.

As she read more about wicked problems, she realized that they also happen in a unique way in tech, especially in four key problem spaces: legacy technology, digital literacy, finance practices, and agile and lean methodology.

Technology and design are not neutral

Technology isn’t neutral — it has both positive and negative outcomes, said Oyelayo-Pearson. Design is also not neutral, she added.

“Our work in tech needs to keep in mind the humans at the end of the product or experience,” said Oyelayo-Pearson. “We are absolutely going to be creating a service that is an opportunity for them or a constraint for them.”

While humans are both the consumers and users of a product or service, anything designers do with the technology now will also have positive and negative outcomes for future designers and developers as they iterate on that product or service.

“We're all aware of legacy tech where, as a former colleague put it, the technology you want in your future is held back by the decisions you made in your past,” said Oyelayo-Pearson. “It's literally like the worst-case scenario for anybody.”

And startups are not immune to legacy technology, she said, because when they don’t have enough money to build what they really want to build, they instead create legacy tech on their first day of the job. That is, they build something quickly now that they can fix later, she said.

When the pandemic locked down the world in March, seniors and people on limited incomes couldn’t stock up on food and were left in a precarious position in the midst of panic buying that left some grocery store shelves empty. Food banks in Canada saw demand for their services surge as millions of Canadians lost jobs due to the pandemic. And while some people turned to online shopping, the experience wasn’t designed for seniors, who faced disappearing time slots and busy pages with a slew of ads, said Oyelayo-Pearson. All that contributed to food insecurity among seniors as they struggled to use a service that wasn’t designed for them.

“We never believed they would buy groceries online because they like to feel the vegetables and touch them and really understand what's going on there. So their needs were excluded,” she said.

As the pandemic lockdown continued and kept kids out of school, new wicked digital problems around education technology emerged. In rural Ontario, for example, unstable internet connections meant some kids couldn’t participate in digital learning as readily as their city counterparts. And across Canada and the world, some families didn’t have enough devices or data to share amongst their children, creating unequal learning opportunities. Oyelayo-Pearson pointed to one story in The Guardian where a mother of six only had one device. Rather than decide which child would use the device for online learning, she opted to homeschool on her own instead.

“The resilience of ed tech has been brought into question with all of this,” said Oyelayo-Pearson. For example, some education technology companies would hold off on including PDFs in their initial release because they’re hard to make, she said. They’re intention was to do it in the future, but that becomes problematic for students who need it now.

Wicked problems and the future of work

And as we look at the future of work, autonomous vehicles and AI will lead to job losses creating further job insecurity, potentially exacerbating another wicked problem: poverty. In a study released June 29, Statistics Canada offered a detailed look at the groups of Canadian workers most at risk of losing their job due to automation. People who are 55 years old and older are at the highest risk of losing their jobs because of automation, as are people without a university degree or college diploma, those with low literacy and numeracy skills, or people who already struggle to make ends meet.

While tech may create unintended consequences and wicked digital problems for the people it was meant to serve, all hope is not lost, said Oyelayo-Pearson. There’s also an opportunity for designers to think about how they frame their work for themselves and others and the impact it can have now and in the future.

“We're actively helping to design the system that has the ability to respond well or respond badly to humanity. And so it's really important that we ground ourselves in the role that we play as individuals,” she said.

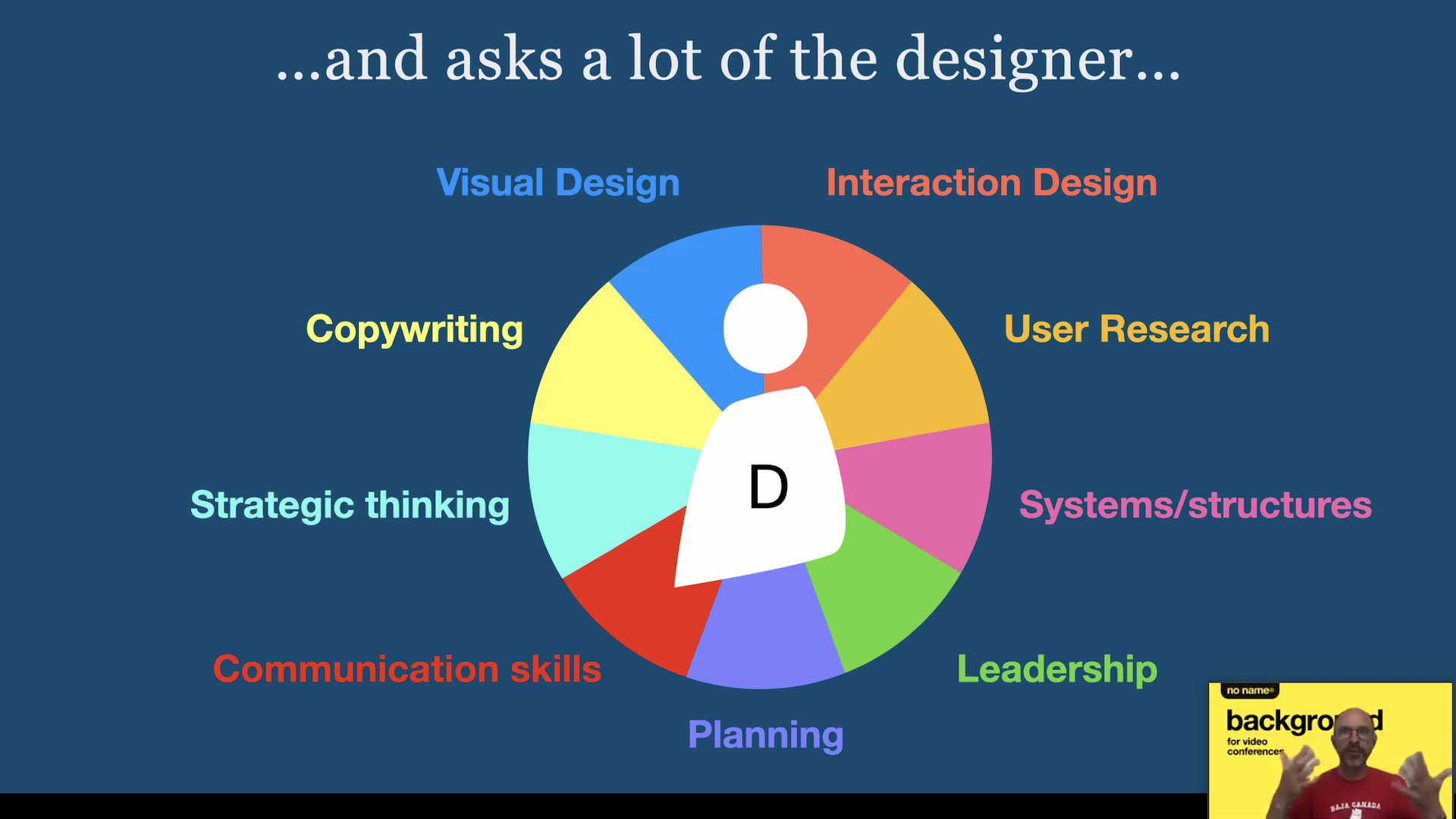

So what can designers do?

She offered several mindsets that designers can adopt moving forward:

• Design greater resilience into the solutions you're working on so there are better outcomes for everyone.

• Embrace consequences and understand the consequences of what you're building.

• Design for equity. Make the case for resilient workflows in the products and services that go out into the world with your design name on it.

• Remember that research allows you to pay attention to the nuances and expose gaps. And learn new techniques like design fiction to challenge the status quo.

• Agency over convenience. You don't want tech to hand hold every person using it, but you do want transparency over convenience, even if it means you lose some customers at the outset.

• And finally, service trumps interface, she said.

“Even if you do not think you're a service designer, you're designing a service. If you do it intentionally, you increase the likelihood that you will design for better resilience,” said Oyelayo-Pearson. “If you do it unintentionally, you may find yourself making wicked problems even worse because your solution isn't considering humans.”

So build resilience into everything you design and create opportunities for tech and the people you're creating it for to pivot, said Oyelayo-Pearson. It's the most important thing designers and everyone in tech can do right now.